· 8 min read

The story of SemApps... and the future of ActivityPods

ActivityPods is built on top of SemApps, a toolkit for developing semantic web applications that dates back to the early 2010s. The technological choices that have guided and continue to guide the development of ActivityPods are intimately linked to SemApps and its philosophy.

SemApps (for Semantic Applications) was created within Virtual Assembly, a french non-profit association founded in 2011, which was initially conceived as a citizen think-tank.

The association’s first project, Idées-Mix (french), aimed to capitalize on 21 ideas proposed by 21 actors, and transform them into concrete projects by linking them up with other actors and resources. But the small team soon came up against the technical difficulties of the project.

The discovery of the semantic web and, above all, the meeting in 2013 with Henry Story (Solid’s historic contributor, who sadly passed away this autumn) gave the project a whole new perspective. The goal of the association was then redirected towards the creation of decentralized software solutions, seen as a means of facilitating cooperation.

SemApps was to become the association’s flagship project. It was initially conceived, not as a toolbox, but as an application to help organizations cooperate, by opening up their data for reading and writing. The first version was developed by Sébastien Lemoine and Romain Weeger, using Semantic Forms, a software made by another member of the Virtual Assembly, Jean-Marc Vanel.

The first instance of SemApps was deployed for a gigantic ephemeral third-place in Paris: Les Grands Voisins (french). It made visible the myriad of organizations and individuals occupying the space, and helped them to cooperate more effectively. It was a large cooperative database.

Naturally, the data was stored in semantic format. There were also features specific to the semantic web, such as the ability to import one’s profile from another instance, or to add links with resources from distant instances. The Virtual Assembly association had its own instance.

Unfortunately, after Sébastien Lemoine left for other adventures, the development of the project came to a halt. The instances continued to run for a few years, but at some point they ceased to function and no one was able to revive them. This coincided with the closure of Les Grands Voisins.

The renaissance

In late 2019, the project was revived by a small team within Virtual Assembly:

- Guillaume Rouyer, the association’s founder and visionary ;

- Pierre Bouvier-Muller, UX designer with a passion for cooperation ;

- Simon Louvet, historic developer and creator of the Semantic Bus (french);

- Sébastien Rosset, a new developer within Virtual Assembly.

Sébastien Rosset was particularly interested in the ActivityPub protocol, which had been standardized by the W3C the previous year and enabled decentralized social networking. Having developed a first server using Symfony, he wanted to give it a new dimension by saving data in semantic format (ActivityPub is intrinsically linked to the semantic web, even if many ActivityPub-compatible apps ignore this dimension).

We had to start from scratch, as the v1 code was unusable. When it came to making the first technological choices, the small team benefited from the expertise of Niko, a veteran developer exiled in Greece.

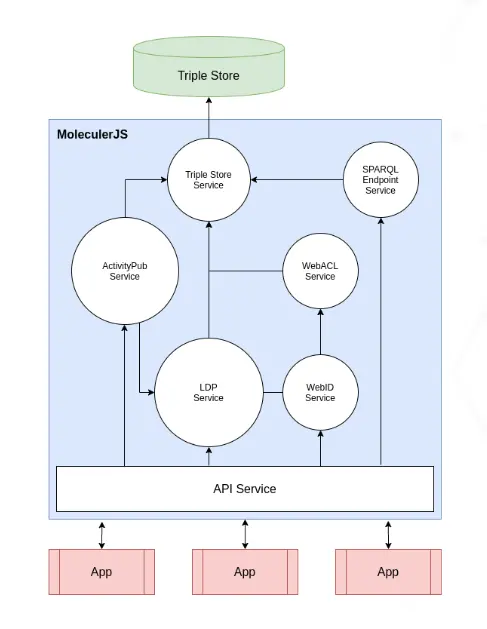

Thanks to his input, it was decided to use Moleculer for the backend. This NodeJS-based framework makes it easy to create microservices, which can remain on the same machine or be deployed on several machines. The architecture fitted in well with our desire to make SemApps modular. This way, users could activate only the services they needed, or develop their own services that could connect to existing ones.

Another important choice was to use Jena Fuseki as a triple store. Although it’s possible to do semantic web without a triple store, the advantage of a triple store is that data is stored directly in semantic format. This means they can be easily queried using SPARQL. As we wanted to develop large collaborative databases, the ability to make SPARQL queries was crucial.

Apache Jena Fuseki was chosen from among the existing triple stores because it was possible to develop extensions. We wanted to offer public SPARQL endpoints that respected the permissions (WAC) granted on resources, and Fuseki made this possible thanks to extensions. This was to be the subject of a major developement for which Niko was to act as leader.

Deploying SemApps v2

After 6 months of intensive work (the first confinement having helped speed up development!), the new SemApps was ready.

Among the first services developed were one to create an LDP server (a REST-based API for reading and writing semantic data) and another to manage the ActivityPub protocol. Both services could integrate WAC permissions but could also do without. Gradually, services were added to facilitate interoperability between instances.

The Virtual Assembly wanted to use SemApps for a purpose similar to the v1: to manage an open, interoperable database. The React-Admin framework was chosen to create a admin-panel-like interface connecting to a SemApps backend. As this was a product in its own right, it was decided to name it Archipelago and keep the SemApps name for the toolbox.

Components for React-Admin were integrated into this toolbox, to facilitate the development of interfaces with semantic data. In use, React-Admin proved to be capable of much more than admin panels, and was used by many sites. Of course, developers were free to use other frameworks, as the frontend was completely decoupled from the backend.

Over the years, instances have been deployed for numerous actors in France wishing to put cooperation at the heart of their IT infrastructure. Examples include Colibris, a major actor in social and ecological transition, Les Chemins de la Transition, a project to create nomadic learning courses, and Destination Oasis, a website for finding accommodation in eco-communities.

Toward Pods

When the Solid project was launched in 2016, the Virtual Assembly community immediately took a keen interest, seeing it as the realization of the vision Henry Story had shared in 2013.

With Solid, users are invited to create a Personal Online Datastore (Pod) on the host of their choice. Then, when they use a compatible application, it stores all their personal data on their Pod. It’s a complete reversal of web architecture as we know it today.

Up until now, the SemApps team’s focus had been on creating tools that encourage sharing and cooperation between organizations. Instead of Personal Online Datastores (Pods), the Virtual Assembly was deploying mostly Collective Online Datastores (or Cods, as we chose to call them in this article (french)).

The focus was thus on facilitating information sharing (with the LDP protocol, but also ActivityPub) rather than on preserving personal data, even if there was a natural interest in the latter. Nevertheless, these remained two very different, even opposing, objectives, which could sometimes give rise to conflicts in terms of proposed functionalities.

The situation changed at the end of 2021, when Sébastien Rosset came up with the idea of proposing Pods integrating ActivityPub natively. Named ActivityPods, this new project was also based on SemApps. In just a few months, the SemApps code was adapted to enable the deployment of Pods, with each Pod having its own dataset on Jena Fuseki.

Applications soon sprang up, such as Welcome to my Place, an app to propose invitation-only events, or Mutual Aid, a classified ads app. In both cases, users would first create a Pod on the host of their choice, and then the app would use this Pod to store their data.

Although ActivityPods was not 100% compatible with the Solid standard (Solid-OIDC is currently being implemented), the project generated a great deal of interest among developers, to the point of being presented in March 2022 at Solid World, the monthly gathering of the Solid community. In June 2023, the project also received funding from NLnet to consolidate the existing code base. This ongoing work is also helping to improve SemApps.

The future: Pods and Cods

At Virtual Assembly, the ActivityPods architecture was so convincing that we began to think only in terms of Pods. Until now, it was “Cods” that were deployed, and users created their accounts on the Cods. But why should their personal data be linked to a particular Cod? Couldn’t they create a profile on their Pod, then share it with the organizations they’re involved with?

Taking this a step further, we realized that Archipelago itself could become an ActivityPods-compatible application. Each organization, instead of deploying an instance on its own server, would choose a hosting provider for its data. And it would then use the Archipelago app (but also other apps) to manage its data and share it with other organizations.

To have real Cods that can be created “on the fly” and function like Pods, we would simply need to refine the rights management interface. A user with a Pod could create a Cod for an organization, and become the Cod’s administrator. He could then grant administration rights to other users.

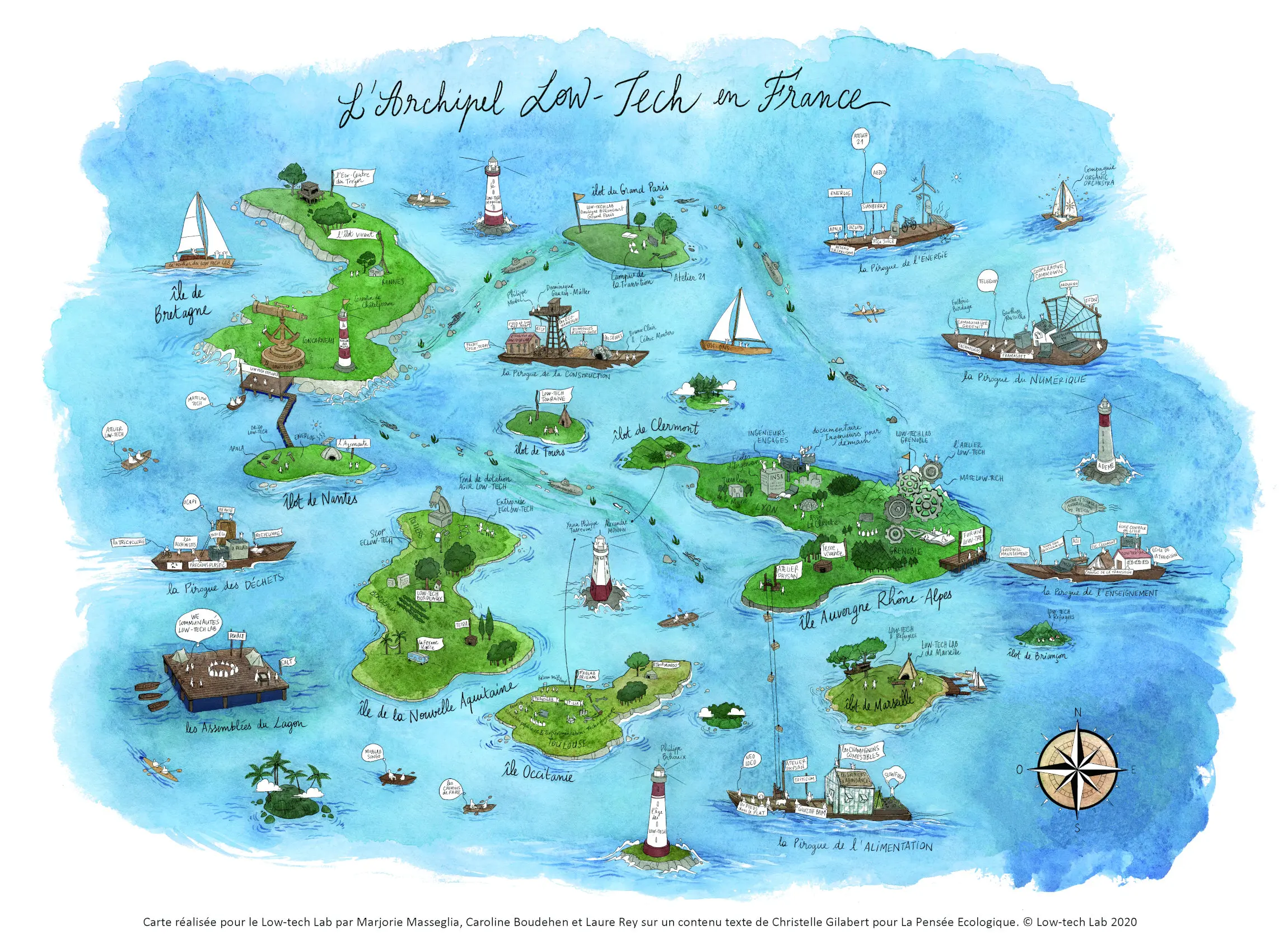

The result would be a constellation of Cods and Pods, all interoperable with each other. Collective data would be on Cods, personal data on Pods. The aim would be to promote exchange and openness, while preserving data sovereignty. These two objectives, which seemed so far apart at the outset, would thus be achieved in this new architecture with revolutionary potential.

There’s still a lot of work to be done, but these prospects are encouraging. Despite our limited resources, we’re confident that the dreams that have been nurtured for almost 15 years within the Virtual Assembly (and internationally, within the Solid and ActivityPub communities) will come true in the next few years, and radically change the way we use the web.